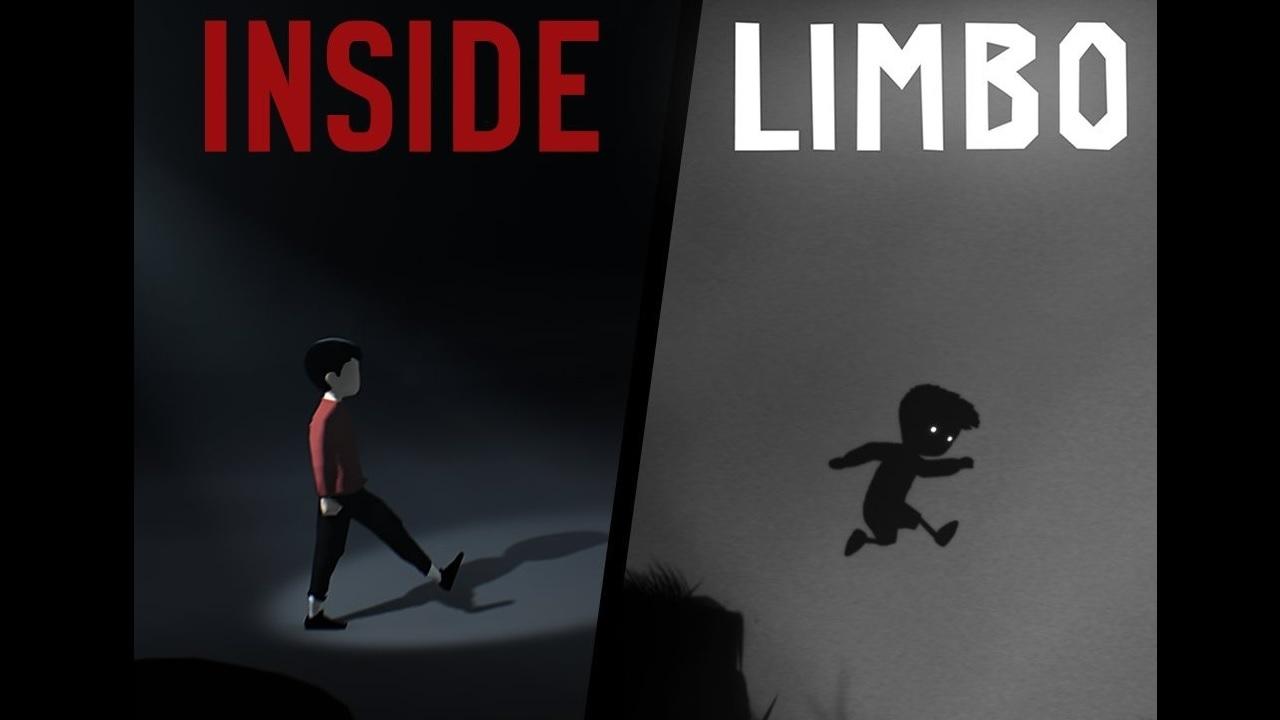

Enemies are meant to be outrunned, or outsmarted. Like Limbo, the gameplay of Inside is modelled after sidescrolling 2D platformers, and in particular the beginning plays like a runner. Here society is totalitarian and people are literally faceless robots exploited for a higher (although unclear) purpose.

The faceless avatar-protagonist also fits nicely with one of the topics explored in the game: totalitarianism. Not only does it suggest that this could be a representation of anyone, like many faceless avatars imply. The inclusion of a faceless avatar-protagonist is here doubly fitting. The color scheme is mostly monochrome and in the rare situation in which colors are used they are bleak. But the game move onwards to other topics such as totalitarianism, identity and control, before moving into more existential issues – if we say more we may spoil the game, but suffice it to say, this is also where a sense of realism breaks. Compared to Limbo the game has a greater sense of realism, at least in terms of social realism: There are no monster spiders here and the immediate feeling of the game is that it reflects some of the realities for refugees in Europe today. You run through the forest, followed by flashlights, dogs and people pursuing you in a car. Kristine: You cannot really understand the game without understanding the aesthetics of it. And it could definitively have pushed against my boundaries a lot more. It could, however, be communicated a lot clearer. I was more intrigued by the game and the concepts it was trying to communicate. Was it? Gross… no, not unless you consider body horror gross. Gross? I thought to myself, I like gross! So, I downloaded it the moment I got home. It wasn’t until a recent Facebook thread reminded me of it, where none other than Tim Schafer was referring to it as gross. Kristian: I knew the game was coming, and had really enjoyed Limbo. So is Inside uncomfortable, profound? It appears that we are mixed in our opinions about the game. My anticipation that this would actually be an uncomfortable or profound game was however raised when I encountered this screen when looking it up on Steam: What I expected was an indie game, probably in the same mood as Limbo, which it in many ways is. I knew Playdead had released a new game called Inside, but that was about it. Kristine: I actually didn’t know much about the game before I started to play. Researchers in the Games and Transgressive Aesthetic have played the game, and we present here our impressions of the game – as a dialogue between project leader Kristine Jørgensen and PhD student Kristian A. This summer, Playdead – developer of the critically acclaimed Limbo – released their much anticipated second game, Inside.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)